*First posted Feb. 1, 2021.

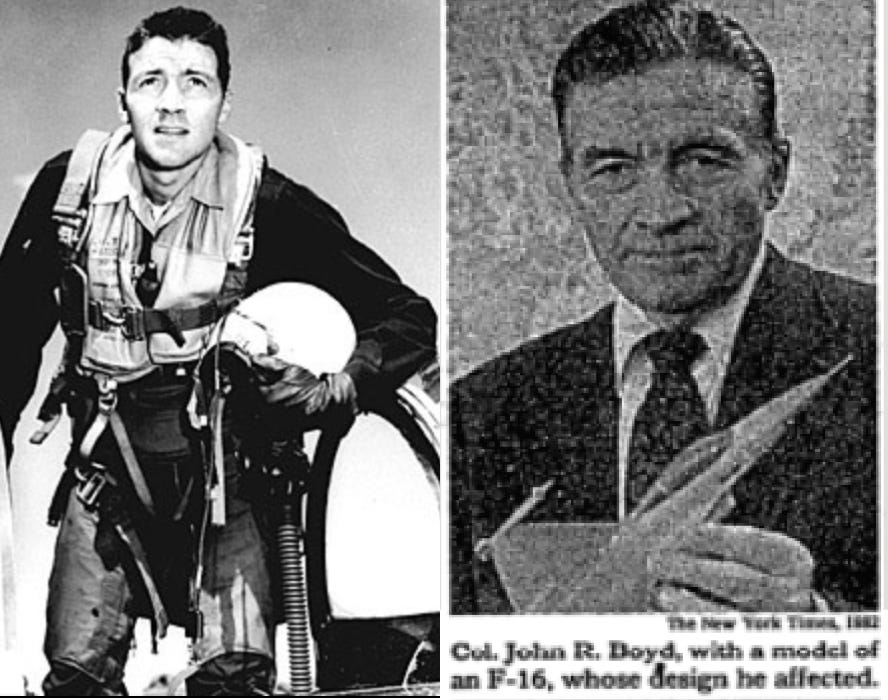

Even for an Air Force pilot, John Boyd had a lot of nicknames.

There was “40 Second Boyd” for his ability to take down all-comers in aerial combat training. He bet he could beat anybody within 40 seconds or he’d pay them 40 bucks. He never paid. He may have been the greatest dogfighting pilot in American history.

There was the “Mad Major,” and even “Genghis John” for his focus and drive to dominate competitors. His conquering spirit got him a conqueror’s honorific.

But the nickname we should remember most was the humblest. For years, leading into his military retirement and beyond, Boyd was known as the “Ghetto Colonel.” It’s what this nickname represents—his personal philosophy on life itself—that truly what set John Boyd apart. He taught us the way to be strategists, not sycophants, a lesson that far too many in the field have failed to learn.

* * *

People mostly know the bumper stickers about Boyd. The snippets of wisdom, the quotes, including:

“If you want to understand something, take it to the extremes or examine its opposites.”

“To be somebody or to do something. In life there is often a roll call. That’s when you will have to make a decision. To be or to do? Which way will you go?”

“Do you want to be part of the system or do you want to shake up the system?”

But if there’s one thing everybody knows about John Boyd, it’s the OODA Loop. There’s plenty of websites to take readers deeper, but the acronym stands for Observe-Orient-Decide-Act. It’s a “time-based theory of conflict” in the words of Boyd’s biographer, Robert Coram (whose book, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, provided the references in much of this essay).

I confess, I’ve never been an OODA Loop guy. It’s great as a philosophy for rapid tactical action in close combat, but that’s about it. It’s often stretched for use in strategic scenarios far beyond its original intent. OODA’s good for gunslingers but not Cold Wars.

Because we know superior tactics doesn’t win wars. The German army out-OODA’d all adversaries in both World Wars, and Germany was defeated both times.

Besides, Boyd’s a lot more interesting when you get past OODA. He showed strategists how to change the game personally to change the organization professionally.

* * *

Let’s let Coram, his biographer, tell this part of the story:

“When Boyd retired as a full colonel with twenty-four years of service, his retirement pay was $1,342.44 [about $6,500 today] per month, plus COLA–the cost-of-living allowance. Even in 1975 that was a pitifully small sum to support a wife and five children. Boyd easily could have followed the route of many senior officers and gone to a well-paying job with a defense contractor.”

“Boyd knew he had to be independent and he saw only two ways for a man to do this: he can either achieve great wealth or reduce his needs to zero. Boyd said that if he can reduce his needs to zero, he is truly free: there is nothing that can be taken from him and nothing anyone can do to hurt him.”

“Boyd stopped buying clothes. The cars that he and [his wife] Mary drove would, over the next decade, become rambling wrecks. He even refused to buy a case for his reading glasses; instead, he carried them around in an old sock. And despite the rising anger of his children, he said the family would continue to live in the basement apartment on Beauregard.”

Offered a job as a Pentagon civilian, Boyd said he wouldn’t take the salary. “Boyd was horrified that he might be called a ‘double dipper’–a man who had both a government pension and a government job.”

“He worked about five years with no pay, before word came down that the Pentagon could not have unpaid consultants. Boyd griped and complained and said he wanted the smallest salary possible, $1 per pay period, but the minimum time a consultant could be paid for and remain on the Pentagon rolls was one day every two weeks. So henceforth Boyd was paid for one day’s work every two weeks.”

* * *

To be a strategist is to tell people what they don’t want to hear. It’s about making choices people don’t want to make. It’s about having conversations they don’t want to have. It’s about advancing unpopular ideas and going against the grain and making people uncomfortable, because, let’s face it, we humans prefer comfortable consensus to strategic coherence.

Boyd’s approach enabled him to finish projects he believed in, projects that mattered, that he never published but delivered as presentations that were highly influential at the Pentagon. They included “Destruction and Creation,” and “Patterns of Conflict,” and when he gave them he demanded several hours of uninterrupted, undivided attention from his audience.

When 4-star officers like the admiral serving as chief of the navy and the general serving as chief of the army asked for shorter versions of the 6-hour briefing, Boyd turned them down. He didn’t need their favor or approval. He had reduced his needs to zero.

Boyd’s life philosophy made him a stronger strategist. So much so that when the US House Armed Services Committee wanted to understand military reform after the Gulf War, John Boyd’s was the first voice they listened to.

* * *

What would John Boyd would think of us in defense nowadays, twenty-four years after his death? I think the Ghetto Colonel would feel disappointment. I think he’d wonder what happened, especially after 9/11.

I think he wouldn’t be surprised that true candor is rare in big organizations like the US Department of Defense. That organizational fear is common. That fear of making “The Boss” unhappy in any way. That the next promotion starts with nodding your head up and down, always, and then to keep doing it for the next one, and the next one. That you can’t step on anybody’s toes, or, as bad, that you can’t be perceived as stepping on anybody’s toes.

If Boyd were still around today, he would have celebrated his 94th birthday just last week (on Jan. 23rd). The Ghetto Colonel’s continued presence might have reminded us that the best path to change the system is to exist beyond the system’s incentive structure.

The irony, of course—for the guy who famously challenged people to be doers and not be’ers—is that who Boyd became enabled him to do what mattered. If you get the be right, you can do anything.

Strategists, look at the Ghetto Colonel’s example. Pay close attention. Your job is to provide expert judgment on the way to tough decisions. When your future’s dependent on senior approval, your judgement gets warped and compromised, and you’re no good as a strategist. Find some way to maintain your independence, shield yourself from the system’s incentives.

For myself, I’ll follow Boyd and retire from the military in a little over a year. My pension will be about 20 percent less than Boyd’s, but our family has no debt, will neutralize our mortgage in the coming months, and will have preserved my GI Bill college benefit for our kids. I may not use an old sock to hold glasses, but we have reduced our needs to near zero.

Like Boyd, I see I can’t change the system from where I am. It’s time to move outside. It’s time to do something.

***

*Post Script, September 2023. It’s hard to believe it has been two-and-a-half years since I wrote the above on Boyd. Interestingly, his lesson speaks louder to me now than it did back then. To be a strategist trapped in a system with poor or painful incentives is to lose your edge, and that’s never a good place to be, and time to move on.